Tides, Ties and Binds

The United Kingdom's shifting understanding of Europe and itself

Tom McTague’s compelling book Between The Waves: The Hidden History of a Very British Revolution, 1945-2016 explores the ebbs and flows of postwar British engagement with the politics of Europe and conceptions of European integration.

This book is on one level a study of the deep roots of Brexit and the persistent unease of the UK within ever closer EEC/EU institutions. The failure of all British Prime Ministers bar Ted Heath to accept the political and sovereignty implications of membership is a recurring theme - the British comfort-zone was to view the institutions solely as a trading block and later a single market. However, the book also highlights the push factors towards European institutions, which drew each Premiership, until 2016, towards acceptance of the need to be in the club. This was comfortable territory for Major, Blair and Brown, but also applied to the Euroscepticism, or indifference to the European project, of Wilson, Callaghan and Cameron. Thatcher’s journey from architect of the Single Market to Euro-disillusionment is more complex territory and, in many ways, the core of the book.

McTague’s arguments are built on a healthy respect for contingencies, and the power of ideas and political organisation to shape unknown futures. These sit alongside the structural challenges the UK faced as a postimperial Union. McTague concludes that unresolved tensions - in economics, defence and culture – mean future British answers to European questions may flow in a different direction.

The book’s premise of uncertain and unknowable futures flows from the epigraph, a wonderfully evocative metaphor by Michael Oakeshott:

In political activity, then, men sail a boundless and bottomless sea; there is neither harbour for shelter nor flood for anchorage, neither starting-place nor appointed destination. The enterprise is to keep afloat on an even keel; the sea is both friend and enemy, and the seamanship consists in using resources of a traditional manner of behaviour in order to make a friend of every hostile occasion.

This attractive mode of conservative politics as conditional and sceptical of grand schemes runs through the story the book tells, but in an uneasy dialogue with the more ideological currents of the British right. Thatcherism, through its economic liberalism and Atlanticism, and Powellite British nationalism, both, in their different ways, did have appointed final destinations in mind.

The book has an unexpected starting point. It is framed by an exposition of men with different conceptions of Europe and Britain who all found themselves in Algiers in 1945. Here Harold Macmillan, Dwight Eisenhower, Enoch Powell, Jean Monnet and Charles de Gaulle framed their differing visions of what postwar Europe should look like, and what role Britain should play. A parallel theme of what a British Gaullism could have resembled, and why it didn’t emerge, provides fresh perspectives on figures from Ted Heath to the Francophile Godfather of Brexit James Goldsmith. The book flows in some unexpected directions, enjoys ironies, and bypasses other topics a reader may have expected to find. It is an enjoyable and stimulating read.

Shifting Unions

Between The Waves also provokes conversations about how Europe as a contested idea - an association, a shared community, or for some an oppositional force - interacts with the idea of the United Kingdom itself, as an uneasy multinational Union. The book is concerned primarily with high politics, and as the British left gradually reconciles itself with the EU the story becomes a history of the British right. It contains fascinating details on the lineage from quiet Euroscepticism to the shouty tautology “Brexit means Brexit” that occurred within the institutions of conservative Britain. This takes the reader into Peterhouse Cambridge, the Conservative Philosophy Group, the Bruges Group, the Adam Smith Institute and, finally, Vote Leave.

It is striking within these conservative circles how often impetus and intellectual clarity emerged from Scottish activists and thinkers. Often Caledonian clarity ran up against ahistorical romanticism from English conservatives. McTague notes:

Time and again in this story traditional right-wing English Toryism finds itself being strengthened by sudden injections of a more robust, even combative, Scottish variant.

When you add this to the story of the modern British liberal-left, you see how disproportionately influential Scots have been in shaping the modern UK. The constitutional reforms of New Labour, and the upper echelons of that party, were overwhelmingly Scottish led: Donald Dewar, Gordon Brown, Derry Irvine, George Robertson, Robin Cook, Charlie Falconer, John Smith, Blair himself, and many others from a younger generation. One concern in contemporary politics is that devolution has largely sidelined Scottish intellectual and organisational leadership from Westminster. The legacies of both the Brexit and devolutions settlements are intertwined and remain muddled.

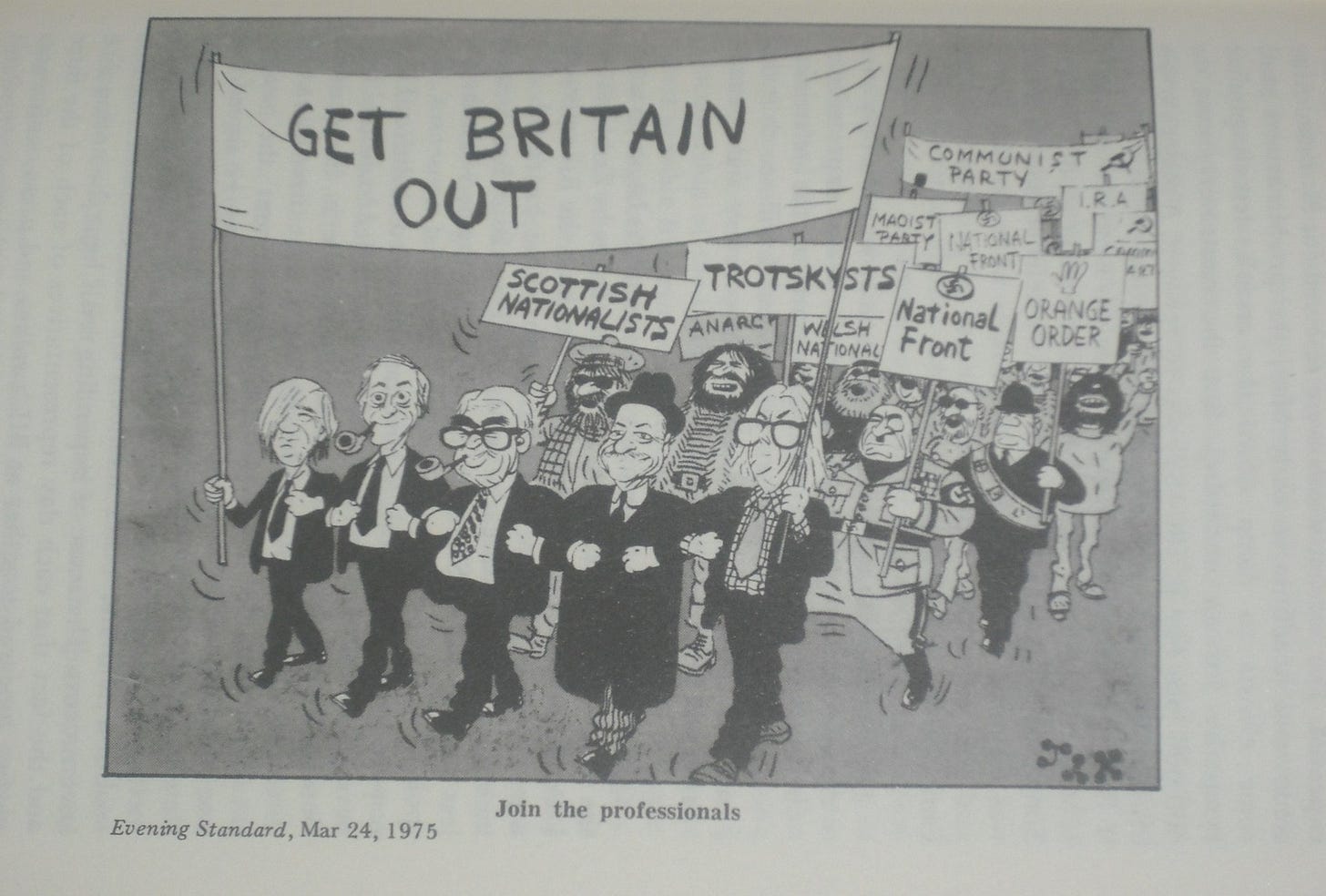

Nationalism is one of the currents of the book. But, as ever, the question is ‘which nation?’ The book details how Scottish intellectual energy driving conservative demands for increased British sovereignty swam in the same waters as conservative literary and academic celebrations of a Deep England – a version of Englishness seeking to be free of the global complications of both Empire and European integration. Rather than a nostalgia for Empire, as some opponents of Brexit suggested, the roots of many strands of Brexit are in this nostalgia for an imagined Britain as an independent nation-state – a status that if it ever existed was limited to the 1950s and Sixties, the period Thatcherites (with some cause) saw as the moment the UK lost competitive advantage over western European allies who formed the original Common Market.

As the work of Paul Corthorn has highlighted, the position Enoch Powell ended up occupying was of a Britain (or sometimes an England) making its way in the world outside of European institutions, free of the Commonwealth (which he was contemptuous of) and anti-American. After losing the opportunity to fulfil his dream of being Viceroy of India, Powell wanted to create a British nation-state, as a signpost towards a return to an imagined past. This would have perhaps been more straight-forward if the nation was England, but by 1974 Powell was MP for South Down. Powell’s notions of the eternal power of the Commons collided with the contested sovereignty of his constituency, and the bruising experiences for Ulster unionists of decisions approved by the Commons and imposed on them against their will and often without consultation - from Direct Rule to the Anglo-Irish Agreement.

The work of (check notes) Walker and Greer

By the time the book moves into the 1990s the focus of Between the Waves shifts away from the national questions inherent within the UK and how they relate to Europe. These questions were, however, not going away, and became the centre of the tumultuous decade of British politics that lasted from the Scottish independence referendum of 2014 until the pronounced failure of British statecraft in the May-Johnson-Truss-Sunak years.

It would be remiss of me not to mention an excellent 2023 publication that addresses this tumult: Ties that Bind? Scotland, Northern Ireland and the Union. Written by Graham Walker and me, it is available at a very reasonable price and has the makings of the perfect Christmas present for someone special in your life. The book reflects on the deep historical, cultural and political connections between Scotland and the north of Ireland – embodied in both what ATQ Stewart called “the Scottish dimension” to Ulster life and the Irish dimensions to Scottish life. My co-author, Graham, has perfectly described the relationship between modern Scotland and Northern Ireland as one of “intimate strangers”.

Our book ends with reflections on the inter-related national questions entangled within Brexit. In post-1945 Northern Ireland and Scotland, Europe has been a revealing lens through which to view questions of national allegiance, where power lies, and notions of democratic consent and legitimacy.

Conceptions of The Nation and The People have always been messy and multi-layered within Great Britain. Northern Ireland’s place in the Union geographically, culturally and politically helps add other layers and caveats to the boundaries and meanings of what it is to be British. Depending on tastes, this can be viewed as a weakness or a strength. As Between The Waves suggests, the future of the UK – with all its asymmetries, partnerships and imbalances - will be entwined with questions of how our continent responds to an increasingly volatile and hostile world.