The Thran Glory of Danny Blanchflower

31 years after his death, the appeal of Blanchflower's approach to football and life endures

In Kenneth Branagh’s romantic Belfast, as we are drawn into a child’s view of the city on the precipice of the Troubles, we see the name Blanchflower painted on a gable wall. That the honour falls to Danny Blanchflower rather than George Best can be attributed to Branagh’s love of Tottenham Hotspur, but beyond tribal football allegiances the Spurs captain deserves pride of place. The sport and wider culture would benefit from a new exposure to the life and ideas of one of the most significant players and unique intellects in the history of British and Irish football.

Twice voted Footballer of the Year in England, and captain of the best sides either Spurs or Northern Ireland have possessed, the bare bones of Blanchflower’s record are impressive enough. However, no list of honours alone defines Blanchflower’s importance. He reached the summit with both creativity and stubborn resolve, while also developing a career as a pioneering writer and commentator, articulating a striking vision of how the sport should be played and how life should be lived.

There are two clichéd templates for excellence routinely celebrated within Northern Irish sporting traditions. First is that of the Gifted Genius - think Best or Alex Higgins – who achieves (fleeting) greatness through instinct, natural ability, and abandon. Alternatively, we have the Honest Professional who makes the most of more limited ability through blood, guts, and selflessness. Blanchflower is different. He combined ability and individuality with dedication, teamwork and an intellectual engagement with the dynamics of his sport. He constantly thought and wrote not only about how he and his teams could improve but also the wider social and cultural purpose of the game. He was a serial winner who held the view that winning was of limited importance.

Bloomfield and beyond

Danny Blanchflower (10 February 1926 – 9 December 1993) was born and raised in Bloomfield, East Belfast. His father John was a shipyard worker and an amateur jazz musician. Unusually for the era Danny’s football genes came from his mother Selina, a star of the pioneering Belfast women’s side Roebucks. Blanchflower had a slow journey up the football pyramid. His early career at Glentoran was interrupted by the Second World War, during which the family home was destroyed in the blitz. Lying about his age, Danny volunteered for the RAF and as a trainee navigator took advantage of a scholarship to study maths, physics and kinetics at St Andrew’s University. He was posted to Canada just prior to the war’s conclusion.

Travel and education deepened his independence of mind and desire for a new environment, but post-war he was 23 years of age before he made it across the water to Second Division Barnsley. Two years later Blanchflower reached the top flight of English football with a move to Aston Villa.

By this time younger brother Jackie (7 March 1933 – 2 September 1998) was already starring as one of Manchester United’s Busby Babes. Contemporary accounts describe Jackie as perhaps a more complete, and versatile, footballer than his brother. It was a huge loss to Northern Ireland football when Jackie’s career was ended by injuries suffered in the 1958 Munich air disaster, just he was approaching his prime at 24 years of age.

After some years understandably struggling with the deaths of friends and teammates, and the physical legacy of the tragedy, Jackie later became known as a celebrated after-dinner raconteur, with his own unique blend of the Blanchflower wit. Late in life Jackie reflected that: "Life has been full of ups and downs, but without pathos there can be no comedy. The bitterness goes eventually and you start remembering the good times… From this distance, even going through the accident was worth it for those years at Old Trafford. I feel happy and at ease now."

Those Glory Glory Days

Back in 1954 Danny began his decade at Spurs. As a creative, intelligent, midfielder under the management of Bill Nicholson, he captained the club to unprecedented success. Defining the ethos, and the myth, of the club Blanchflower affirmed that: “The great fallacy is that the game is first and last about winning. It is nothing of the kind. The game is about glory, it is about doing things in style and with a flourish, about going out and beating the other lot, not waiting for them to die of boredom.” As the first English club in the twentieth century to win the domestic Double, in 1960-61, then winning repeated FA Cups and becoming the first British side to win a European competition, the 1963 Cup Winners’ Cup, Blanchflower’s Spurs combined creative attractive football with phenomenal success.

Internationally Blanchflower captained Northern Ireland to the quarter-finals of the 1958 World Cup. It was a remarkable achievement, qualifying ahead of Italy and defeating Czechoslovakia and drawing with West Germany in the finals. This side of Peter McPharland, Harry Gregg, Jimmy McIlroy and Danny had a collection of world class players, even without the much-missed Jackie, but manager Peter Doherty and the captain acknowledged that a Glory Glory ethos had to adapt to Northern Ireland’s relative lack of resources. The side’s class was combined with the resilience, humour and team spirit common to all successful Northern Ireland sides, qualities embodied in Blanchflower’s famous quip: “We aim to equalise before the other team score. We should get our retaliation in first.”

Off the pitch Blanchflower’s rise up the pyramid was accompanied by regular fights with directors, managers and others in power. His deep suspicion of hierarchy and articulation of players’ rights made him an unpopular figure for authorities in the deferential era of the maximum wage. Throughout his life he was also infuriated by the failure of British football to modernise its methods and tactics.

The passion inspired by Blanchflower’s Spurs team is captured in the 1983 film Those Glory Glory Days. An autobiographical coming-of-age drama written by Julie Welch, it tells the story of a woman football journalist disillusioned by misogyny in her profession and reflecting on her teenage love for the Double-winning side and Danny in particular. In a touching cameo Blanchflower responds to the journalist’s worry she is “daft” to seek a career in football by advising her: “It’s nice to be a bit daft at times - that’s how we learn. If you want to change things you’ve got to fight for it, if you want to get into the team.”

A beautiful illusion

Openness to learning and new ideas was key to Blanchflower’s worldview. As the writer Jon Spurling has observed, Blanchflower’s deep interest in culture flourished while he was a player at Spurs and is reflected in his friendship with the classical musician and critic Hans Keller. A football obsessive, Keller saw Blanchflower’s Spurs as: “the equivalent of an orchestra playing at perfect pitch – individually brilliant, allowed to express themselves”. In turn Blanchflower saw Keller’s taste in music and football as simpatico: “Hans analysed football in a particular way. He wanted to see something with rhythm and drumbeats and excitement.”

A trained electrician from his days working at Gallaher’s in Belfast and then the RAF, Danny remained open to other professions and intellectually curious throughout his playing days and beyond. In Barnsley he took evening classes in economics and accountancy, where he became friends with fellow student and future Labour Cabinet Minister Roy Mason. Then in 1954 he began a thirty-year career as a writer and columnist – first with the Birmingham Mail and then numerous other publications, most notably regular columns in the Sunday Express and New Statesman. He was the first elite footballer to write his own columns and an autobiography. He did so without the supervision or the approval of his clubs.

Early on Danny warned readers his approach was “to be honest, and often contradictory and argumentative”. He added: “I reserve the right to change my mind whenever I want to as I don’t mind admitting I have much to learn. But let me assure you I’m awful hard to convince.” On the pitch and in print Blanchflower was a stylist with a romantic conception of the game: “Whether you’re a player, manager, trainer, director, supporter, reporter, kit man or tea lady, football possesses the power to make the week ahead sparkle with a sense of joyous well-being.”

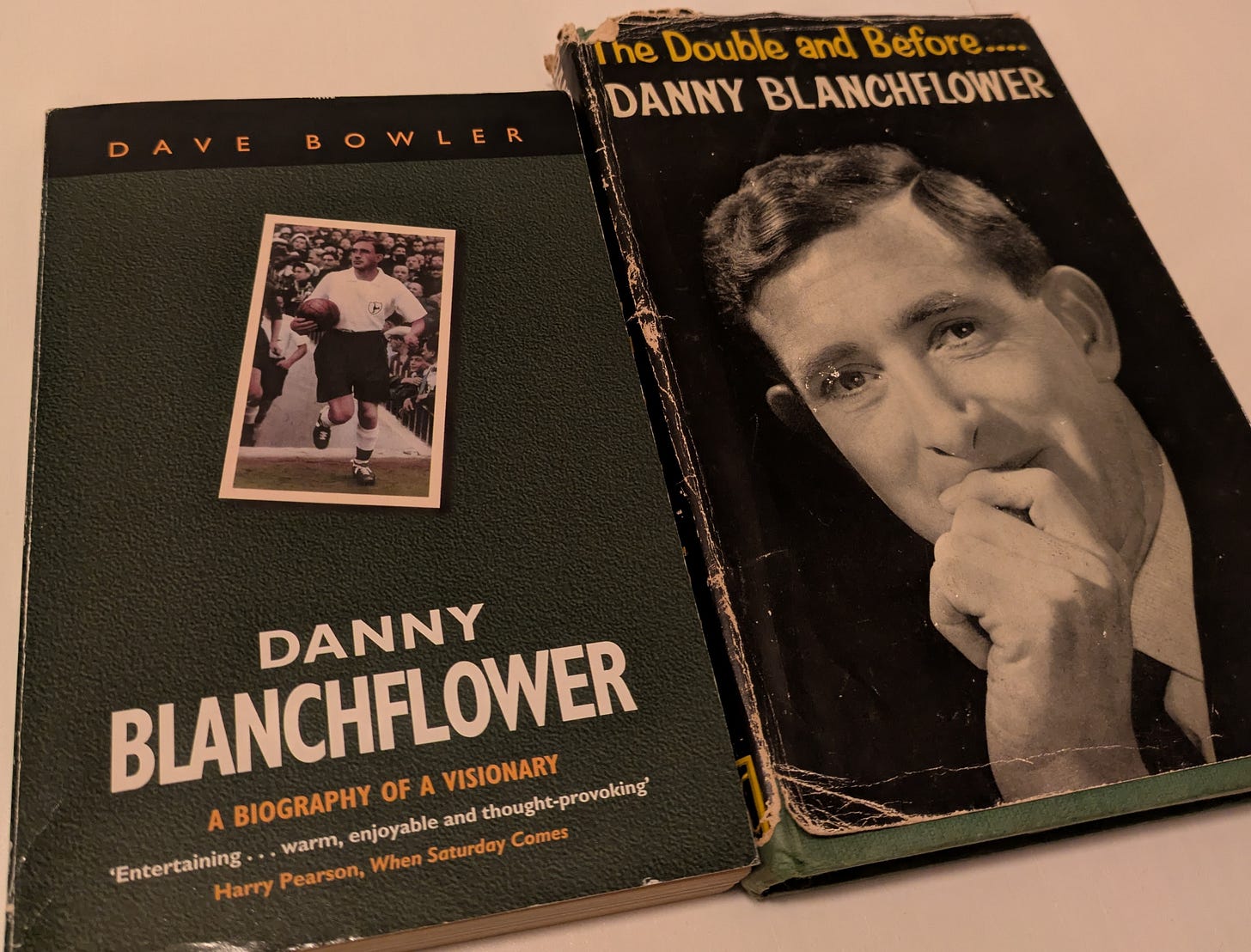

Blanchflower also dismissed the view that sport could be easily separated from wider social concerns. His biographer Dave Bowler singles out a New Statesman column concerning a Muhammad Ali-Joe Frazier fight as an exemplar of Blanchflower’s craft as a writer:

Cassius Clay, grandson of a slave, has wholesome roots. Muhammad Ali, stepson of a Black Prophet, has heavenly ideals. There has never been a performer like him before. He has out-talked the journalists, out-promoted the promoters and out-boxed the contenders. We have come to scrutinise Superman, to see his feet of Clay…. Frazier catches Clay in the last round and sends him to the floor… It is a terrible blow for optimists. What they have lost is a beautiful illusion, that a man can be so good he can leave the pack and all its pedestrian little ways behind. The boxers and administrators have claimed back their game.

Legacies

In a short largely unsuccessful managerial career, with Northern Ireland and Chelsea, Blanchflower remained drawn to playing attractive football despite managing squads much less talented than those he had captained. His failure as a manager could be attributed to an outdated approach, a romantic out of step in an era of rigid 442s, but there was also a sense that in the dug-out Blanchflower lacked the focus needed to succeed as management. He earned immense affection and admiration from his Northern Ireland players, but it took the relentless drive of his successor Billy Bingham to forge the side’s glorious 1980s.

Back home Blanchflower was also increasingly a reminder of a past era. In his confidence and style, he symbolises the now largely forgotten qualified optimism of early Sixties Northern Ireland. There was no Ulster cultural cringe about Blanchflower - he knew who he was, where he came from and what he stood for. One aspect of this confidence was a comfortable, and complimentary, British-Irish identity. As with Protestant characters in Branagh’s Belfast, this was a natural self-identification for many from Blanchflower’s background, before the horrors of the Seventies saw a quick retreat from Irishness. That otherwise informed critics of Belfast judged characters in the film identifying as Irish as evidence of either Branagh’s “wish-fulfilment, or ignorance” shows how quickly traditions and identities can change, be reinvented and misremembered.

During the Troubles, culturally Blanchflower in some ways became a figure lost in prelapsarian Ulster. A Northern Ireland from before colour television and the car bomb - the Lost Province of Tom Paulin’s poem.

British and Irish football also rejected many of the footballing principles dear to Blanchflower. However, in more recent times positive football with a lineage you can trace to the Sixties Spurs team has become the new norm of how to win. Echoing his emphasis on creativity and intelligent use of space, Northern Ireland now has a sprinkling of promising young technically gifted footballers. They could do a lot worse than follow Blanchflower’s approach to the game.

Enigmatic, and prone to contrariness, Blanchflower defies caricature. He was both a thran individualist and a deeply committed and popular team-player; an incurable romantic, cynical about his industry; a moderniser who regretted football’s commercialisation; an extrovert public commentator with a carefully guarded private life, who famously told the BBC’s This is Your Life to get lost.

Speaking to New York magazine about Blanchflower, Kenneth Branagh focuses on: “how singular he was… There’s something about that character that is very Northern Irish. Some would call it belligerence; some would call it strong-minded and sort of inspiring. He had a strong position and held it”. In his character, contradictions, style and achievements Blanchflower embodies much of who the Northern Irish are, or can aspire to be.